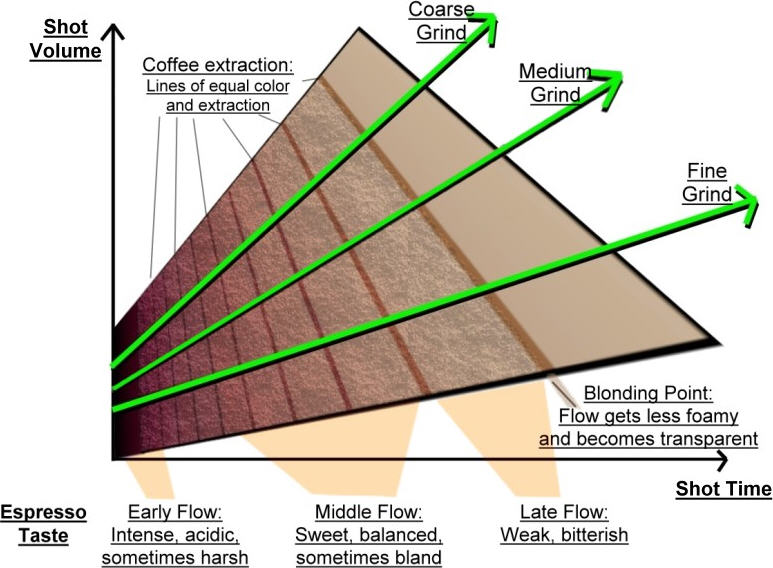

When talking about espresso technique or dialing in a particular coffee, I often talk about cutting a shot based on the blonde or blonding point, rather than time. I do this because watching for that blonding point will provide a good indication of when the coffee is done extracting or when it's approaching that point. I then use time as a reference rather than a control.

Why

If my grinder is set way too fine when trying a coffee for the first time, and I stop the shot at say 30 seconds, I may only get say, a sour 12 grams of espresso from an 18 gram dose. Or if my grind was too coarse, and I was shooting for 30 seconds, the shot may actually be finished extracting, and taste good at 23 seconds. So, I really try and let the coffee tell me how it's doing, and then use taste to know how to fine tune.

I run into both of these examples fairly often. In both cases, I typically drink the shot after I cut it off at it's blonding point. I reference the time and also the final beverage weight. Basically, I'm not pulling shots to a specific beverage weight or time. For the first shot that ran really slow and tight, shots that run this long are typically going to be over extracted if anything. But, I'm also taking note of the beverage yield (mass) and just how it tastes, assuming it's not great at those parameters. Say it has great texture and mouthfeel and balance, then I'm probably going to want to hold that yield and then shoot for that beverage mass on the next shot. But say it's also supposed to be a fairly fruity forward and sweet single origin, and I'm primarily tasting nutty caramel flavors. Then I know if I speed up the shot it should help to get me in that range. So, I coarsen the grind, holding the same dose, and targeting the same yield, but at a faster flow rate. Cutting this shot at the blonding point, results in a 32 second pull.

Sticking with this same example, if that 32 second shot was using something like Onyx' Southern Weather blend, that recommends 19 grams in to 40 grams out in 25 seconds, even if that tasted good, I'm probably going to speed the next one up and see what happens. So, knowing that it took my last pull 32 seconds to reach blonding, and that I'm shooting for a higher yield over 1:2, I know that I need to really coarsen the grind to speed up the flow and extraction. In this example, it might also be an indicator to reduce your dose, keeping the same target brew ratio (could be 18 grams in to 37.8 grams out, the same 1:2.1 ratio). (I propose reducing your dose, because in many cases you don't know what size baskets the cafe is using and/or what grinder. If the roaster uses a grinder that produces dense grounds, they might be able to dose more in the basket than if you have a grinder that produces really fluffy grounds.) In this instance though, I'm using time as a reference as to when I want the coffee to reach 40 grams, or a 1:2.1 ratio, as this must be the degree of extraction the roaster feels best represents the coffee.

What Else?

Pulling shots referencing the blonding point can also allow you to manipulate the attributes you're pulling from that coffee. Again referencing this post and the Espresso Rule of Thirds, if a coffee is become weak, dilute, and/or bitter, you might be better served by ending the shot before it reaches the blonding point. This will allow you to capture more of the thicker, crema infused espresso, and omit the thinner, watery yield at the tail end of an extraction. When pulling shots with a bottomless portafilter, you will begin to be able to recognize the changes in thickness or texture and color in the stream, to better "read" the extraction and know when to end your shots.

Time also serves as an indicator or variable to reference for control. Once you have a coffee dialed in to your liking, keeping the shots hitting the same yields and blonding in the same time range will ensure you're staying consistent.

But Really, Why?

I bring this up because I often see new baristas frustrated that they cannot get the pull to be 1:2 in 30 seconds, or 2 ounces in 30 seconds, or taste good in 30 seconds, or whatever arbitrary parameter they have been told espresso should be. When in reality, every coffee will be different, and some coffees can really taste good when pulled to a variety of different parameters. So by monitoring the blonding or color of the extraction, you have a greater chance of pulling drinkable shots, no matter the parameters, which will provide more useful feedback for what adjustments need to be made.

I've also had some shots run very slow or long on time that tasted very good. This happens when using a new coffee and the grinder is set too fine, but maybe I pull a shot that runs 42 seconds, but end it at or before the blonding point, typically resulting in a more ristretto shot. Sometimes, these shots are very tasty, syrupy, dense, and rich. Had I ended the shot at 30 seconds, I would have gotten a very small yield, and most likely more sour and under-extracted shot.

There's Always an Exception

The expression, "there's an exception to every rule," doesn't receive an exemption from this entire post. In general, monitoring and ending extractions based on the color, flow, and blonding of the shot serves extremely well for efficiently dialing in and "reading" the coffee to know what parameters need to be changed. But, there are times when pushing an extraction beyond the blonding point also produces good results. You see this a lot with lightly roasted "third wave" or "Nordic style" coffees and shots that typically have higher, lungo, brew ratios. In these instances, that last third of the more watery, bitter, solubles may be needed to tame the otherwise acidic and bright attributes of a very lightly roasted coffee. Watching the flow in these instances can still prove valuable to ensure those shots are still extracting evenly to produce balanced results.

Isolating one variable in the inter-dependent equation that creates good espresso can be a bit cumbersome to explain, but hopefully this post will serve as another tool or trick to better understand espresso and how to efficiently dial-in. If you have any questions or comments, please leave them in the comment section below, and thanks for reading!